- Home

- Charlie Engle

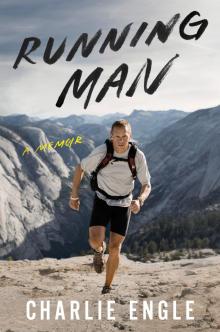

Running Man

Running Man Read online

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

* * *

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Momma

Bid me run, and I will strive with things impossible.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE,

Julius Caesar

PROLOGUE

I always heard the keys—those awful jangling keys—coming toward me, then fading as the guard moved down the corridor. I learned to block out the big bald guy who banged on his locker half the night and the scrawny dude in the corner always yelling something about Jesus. But no matter how exhausted I was or how hard I had crammed the foam earplugs into my ears, I heard those damn keys. It wasn’t the sound itself that got me; it was that the keys were attached to a guard—and where there was a guard, there might be trouble.

The keys meant it was 5:00 a.m.—head count. I peeked out from under the corner of the blindfold I had made with a strip of gray cloth ripped from a pair of old sweatpants. Lots of inmates left their lights on all night; some were reading or writing, some prowling around, doing things I was not interested in knowing about. The blindfold helped me escape all that. I saw the guard moving away from my cellblock. Good. Not my turn to be harassed.

I lifted the cloth off my eyes, dug out my earplugs, and lay motionless on my top bunk, listening to the two hundred other men in my unit stirring. My cellmate, Cody, an affable kid who had been slammed with a ten-year sentence for buying weed, was still snoring in the bunk beneath me. Through the high, dirt-flecked double-paned window in my cell, I could see a square of black sky.

- - - -

Just before I reported to Beckley Federal Correctional Institute, I had been a guest speaker at a big AA meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina. At the refreshment table, a burly, tattooed guy came up to me and told me to make sure I got a nickname in prison.

“Why’s that?” I had asked as I helped myself to an Oreo from a paper plate.

“You get yourself a nickname so that when you get out of the joint and you’re walking down the street and somebody yells out your prison name, you ignore that son of a bitch and keep on walking.”

In the three months I had been locked up, I had encountered a Squirrel, a Shorty, a Pick-n-Roll, a Swag, a Gut, a Tongue, a Beaver, and a Glue Stick. They called me Running Man. I was the middle-aged white guy who ran laps alone on the quarter-mile dirt track in the prison’s recreation yard, past the smirking smokers and the guys playing hoops. When we were in lockdown, I was the fool pounding out miles on the hard floor next to my bunk.

“You don’t belong in prison,” an inmate I knew as Butterbean said after watching me run in place for more than an hour. “You belong in a fucking insane asylum.”

Running Man. They couldn’t know how well it fit me. I had been running all my life; trying to find something, trying to lose something. Running helped me kick a ten-year addiction to cocaine and had kept me sober for going on twenty years. Running saved my life—and then it gave me a life. On the outside, people in the ultrarunning world knew who I was. I’d run across the Sahara Desert, setting records along the way. I had been on Jay Leno. I had paid sponsorship deals, now long gone. I was getting hired to give inspirational speeches to auditoriums full of pharmaceutical salesmen, war heroes, corporate bigwigs, and weekend warriors. In prison, running—thinking about running, reading about running, writing about running—was the only thing I had left.

One morning, just before 10:00 a.m. head count, I was on my bunk reading a Runner’s World magazine article about Badwater, the 135-mile ultramarathon that takes place in Death Valley, California, every July. Lots of people think it’s the toughest race in the world, and I wouldn’t argue with them. The course starts below sea level and ends at Whitney Portal, a lung-busting 8,300 feet up Mount Whitney. The blacktop in the desert is so hot—often more than two hundred degrees—it can melt the soles off your shoes and blister the skin off the bottoms of your feet. I’d run Badwater five times and placed in the top five all but once. I loved that race and the people who ran it. I thought of myself as part of the big, crazy Badwater family.

I was still thinking about Badwater when I went out to run that afternoon. I had two hours before I had to be back in my cell for 4:00 p.m. count. From the grassy place where I always did my warm-up stretches, I could see the rooftops of a few houses on a distant ridge. Sometimes I even heard music drifting up from the wooded valley below. The track was the only place I could almost convince myself that I wasn’t in prison.

I started to run, easy at first, then faster. I felt the sun on my face. I let myself think about Badwater, about the wavering heat and the beckoning horizon. I pictured the hazy mountains looming over Furnace Creek and the furrowed dunes of Stovepipe Wells and that long, desolate climb up to Townes Pass. I remembered the desert light: russet at dawn, lavender at dusk. I thought about winding my way up Mount Whitney, knowing that with every S-curve, the torturous climb was closer to being done. And I remembered the pain. I ached for that exquisite, illuminating pain now, the kind that exposes who you really are—and asks you who you want to be.

About five miles into my run, I picked up the pace. And I started to hear something in my head I had heard before—a sound like the whir and clatter of a spinning roulette wheel, with the metal ball rolling in the opposite direction of the wheel, waiting to drop into play. You think you know where the ball is going to land, but then it bounces around and settles in a place you never saw coming. In my mind, I saw the ball ricochet and hop and, finally, land. I stopped running. Breathing hard, I clasped my hands behind my head and looked up at the sky. I would run Badwater this year after all. Yeah. Hell, yeah.

I would run the race on this shitty dirt track. I calculated the distance in my head. It would mean doing 540 laps, probably about twenty-four total hours of running over two days. I’d have to call in some favors and I’d have to fit it all in between head counts, but with some luck, I thought I could do it. I started to run again and felt a familiar happiness wash over me. It was the buzz I always got when I committed to a big race. This time it came with an oddly exhilarating—and undeniably ironic—sense of freedom: there were no entry fees, no application, no crowds, no airport security lines, no Twitter feed, no fund-raising, no finisher’s medal, no pressure. All I had to do was run 135 miles. On the morning of July 13, 2011, the first day of the Badwater race, I would be standing on a starting line of my own.

CHAPTER 1

You loved me before seeing me;

You love me in all my mistakes;

You will love me for what I am.

—LUFFINA LOURDURAJ

I was born in 1962 in a small, backwoods town in the hills outside Charlotte, North Carolina. From the moment I could walk, I was a free-range kid. My mother and father were nineteen-year-old freshmen who met on a cigarette break during a summer-school literature class at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Richard Engle, my father—lanky, six feet three inches, clean-cut, in pressed khakis and button-down shirts—played freshman basketball at UNC for legendary coach Dean Smith. Rebecca Ranson, my mother—five feet two inches, unruly short brown hair, dark eyes, a budding playwright—was the daughter of an all-American runner who became a revered track and cross-country coach at UNC. But my mother’s high school years had not been spent on a playing field or a cinder oval; at sixteen, she’d gotten pregnant and been sent to a home for unwed mothers, where she stayed until she delivered a baby g

irl, whom she gave up for adoption. I didn’t find out I had a half sister until decades later.

My parents divorced when I was three years old. My father joined the Army in 1966 and shipped off to Germany. I didn’t see him again for more than four years. I found out later that he and my mother had agreed to not say bad things about each other in front of me—which explains why, from the day he left, my mother rarely mentioned him. He just disappeared. My mother threw herself into her schoolwork and her plays—and into protesting every injustice that rankled her. And North Carolina, in the mid-1960s, had a hell of a lot to get worked up about.

Momma remarried. Her new husband, Coke Ariail, was a director, producer, actor, photographer, painter, and sculptor whose favorite motif was my mother in the nude. A gentle man from a traditional Southern family, he had the impossible task of trying to replace my father. I ignored his rules and laughed off his punishments. We moved five times before I turned ten: Coke and my mother always found a new theater group to organize, a new degree to pursue, another wrong to right. September after September, I felt like a freak: the new kid with the scraggly, shoulder-length hair and the hippie parents, who spent his Saturdays not at Little League practices and games, but attending avant-garde plays and marching in antiwar protests. When court-ordered desegregation started, I rode the bus with the black students and befriended a soft-spoken boy named Earl, which, in the eyes of my conservative classmates, made me even more of a weirdo.

Just before I started fourth grade, we moved to the countryside outside Durham into a one-story house with peeling paint and a sagging front porch. My mother loved the place—she said it had “character” and “good bones”—so I said I loved it, too. Every month, I got to take the $100 rent check over to our landlord’s place across the cow pasture that separated our houses. I felt like James Bond running across that field, hurdling electric fences, leaping over manure piles, and swinging wide around the bulls. I arrived at the Wimberleys’ panting, my hair matted with sweat, tattered shorts drooping off my skinny hips, my legs splattered with mud and bits of grass. Sometimes they invited me in for cold cow-tongue sandwiches and cucumbers from their garden.

Coke and my mother were directing plays at the local theater—artsy and edgy stuff they had written themselves. They threw a lot of cast parties. On those nights, I’d sit in a beanbag chair in my bedroom and watch Johnny Carson, turning the volume up to drown out the noise. I kept the door shut, too, because the house smelled weird: pot and incense mixed with the chemicals from Coke’s little darkroom. I never missed The Tonight Show, even on school nights. I liked Johnny, but I watched it mostly for Ed McMahon. I remember thinking he’d be a great dad with that big carnival-barker voice, that jolly rolling laughter. I imagined him coming in the front door at family gatherings.

“Where’s Charlie?” he’d boom, first thing. “Where’s my boy?”

When Johnny and Ed signed off for the night, I often padded out of my room, hungry and thirsty. By then, the party had usually spilled onto our front yard with the speakers facing an open window. I’d peer past the big moths banging on the screen door and spot my mother twirling in a long skirt while Coke danced with everyone and no one.

I remember one night making my way through the living room, stepping over empty bottles, guitar cases, and sandals on the way to the kitchen. I stopped in front of the sofa. A girl was lying there, one arm flopped awkwardly toward the floor. She was snoring. On the low table in front of her were two open bottles of beer, both still more than half-full. After a few seconds of watching her breathe, I went to the kitchen and opened the refrigerator. All we had was powdered milk mixed up in a jug—I hated that stuff—and Coke’s homemade orange wine.

The record started to skip. I walked back into the living room, lifted the arm on the turntable, and put the needle down. The girl on the sofa was still out. I picked up one of the open bottles, sniffed it, brought it to my lips, and took a gulp. It tasted bitter, but I took another swig. I finished the first bottle and picked up the second. The beer made me feel warm and floaty and calm, as if someone had laid a magic hand on me and said, “See there, Charlie, nothing to worry about now.”

On that humid late-summer night, with Janis Joplin wailing on the stereo, alcohol planted a little flag in my brain and claimed that territory as its own.

- - - -

About a half mile into the dense woods behind my house sat a cool, deep pond surrounded by pines, scrub oak, and azaleas. I spent hours at that pond, watching water bugs pulse between lily pads as big as Frisbees, swatting mosquitoes, skipping rocks, and fishing with a cane pole. When I got hot, I peeled off my clothes and swam, then lay on a warm rock and dried off in a patch of sunlight. Those woods were a place to dream—of places I’d rather be, of people I’d rather be. I was Marshal Matt Dillon, Detective Joe Mannix, Kwai Chang Caine practicing my kung fu moves. And I was Jonny Quest—oh, how I loved Jonny Quest—jetting off from Palm Key with my brilliant father, Dr. Benton Quest, on some supersecret world-saving mission to Tibet, Calcutta, the Sargasso Sea.

One afternoon at the pond, I heard a low roll of thunder. Greenish storm clouds were boiling above the treetops. Leaves began to rattle in the wind. I felt one raindrop and another and then a wall of them. I started for home, darting between trees, peeling off my T-shirt as I ran. When I emerged from the woods, I saw a jagged finger of lightning reach down to the field in front of me. The thunder, which had been distant, now boomed above my head. The storm seemed to be on top of me, matching my pace as I ran. I hopped a fence, leaped across a ditch filling with frothy fast-moving water, and cut through the long grass in our yard. I saw my mother standing in the porch doorway waiting for me. Waving my shirt over my head, I hollered and she waved back.

“I’m staying out here!”

“What?” she shouted, and cupped her hands to her ears.

I ran to the foot of the stairs, stripped off my shorts, balled up my drenched T-shirt, and tossed them up to her. She caught them and laughed.

“I’m staying out here!” I yelled again.

I dashed back out wearing only my cotton underpants. Yelping above the thunder and rain, whooping with every lightning flash, I sprinted around the yard. I brushed my hand against an overgrown honeysuckle vine and released its sweetness into the rain. I was soaked to the skin, but I felt free and smooth and happy. I wasn’t scared of the storm. I was making my momma laugh and cheer. I will remember this always, I thought—the way it feels to run until you can’t run anymore, the way it feels to not be afraid.

- - - -

The summer of 1973, my mother decided to move us to Attica, New York. She had been outraged by the Attica prison riot two years earlier, which left forty-three people dead—most of them inmates gunned down by prison guards from thirty-foot towers. Momma had been doing theater workshops with inmates in North Carolina prisons, crafting their lives and struggles into serious plays. She applied for and received a one-year grant to do the same at maximum-security Attica. The riot had started on her birthday—a sign, she said, that she was meant to go there.

Momma and I piled into our yellow VW Squareback, stuffed to the roof with our belongings, waved good-bye to Coke, who was reluctantly staying behind, and drove north to Attica. Coke told me later he thought it was a huge mistake, my mother taking me up there, but he was working all day and trying to do theater at night and had no way to take care of me alone.

We lived over a bakery in a tiny apartment that smelled of cinnamon and fresh-baked bread. My mother slept on a mattress on the floor of the only bedroom; I slept on a ratty sofa in the living room. A railroad track ran behind our place, and every morning at 6:30 a.m., a train rattled by, blowing its whistle. That train was my alarm clock, especially on those days when Momma got snowed in at the prison and couldn’t get home. Some mornings, I would skip school and hang out down by the tracks with kids playing hooky or those who’d already dropped out. Most o

f their parents worked at the prison as guards. We killed time by stacking pennies on the rails and waiting for trains to flatten them. Sometimes, one of the older boys passed around a joint or a bottle of brown liquor. I didn’t like pot—it made me slow and sleepy—but I liked booze. A few times I drank so much with the kids at the tracks I puked, but that didn’t stop me. When I drank, relief washed through me; from what, I didn’t know.

One day, my buddies and I spotted a man running alongside the last car of a slow-moving freight train. We watched him jump up, grab a handle near the door of a boxcar, and swing his body up and through the opening. Our mouths hung open as we watched that train disappear down the tracks.

I decided at that moment I was going to hop a train. I didn’t tell any of my delinquent friends because I knew that if I failed or chickened out, I’d get teased about it. A week or so later, I worked up the courage to run beside the train and discovered it was much harder than it looked. The rocks in the rail bed were uneven and the railroad ties awkwardly spaced. I tripped and fell and landed about six inches from the train’s moving wheels. I should have quit right there. Instead, I worked on my timing and figured out that if I stepped on every other tie as I ran, I could keep up with the train.

One Saturday morning, Momma was at work and I decided this was the day. I threw on my father’s old, way-too-big-for-me Army jacket—one of the few things he’d ever given me—and ran down to the tracks. As a train approached, I hid in some bushes and watched the first few cars pass. When I saw the open doors of a boxcar, I ran, quickly pulling even with it. I leaped at the open doorway and threw my body forward, landing hard on my stomach. For one agonizing second, I teetered, half-in, half-out, and then found a finger hold in a space between the floorboards and pulled myself in. I rolled over onto my back, breathing hard, buzzing with the rush of what I had done.

Running Man

Running Man